- How Much Do You Follow The Armenian Media ?

- Do You Think Armenian Youth Federation Has Nothing To Do With Armenia (Please See Photo Below:Armenians Demand "Recognition, Reparations, Restitution" During Armenia-Turkey Match Sep 2008)

- Do You Believe Armenian Government/People Do Not Want Land & Monetary Compensation Although How Poor & Desperate Armenia Is ? (Armenian Government/People Can Hardly Survive With The Handouts Of Us & Other Funding. Aren't They All Practically Begging To Get The Border Open In Order To Cultivate Some Border Trading ? )

- Are You Naïve Enough To Believe That Armenians Want Just An Apology?

- Do You Think Prof Baskin Oran Should Have Read This Before Writing His Article titled " From Apology Campaign To Armenians Day in France " ?

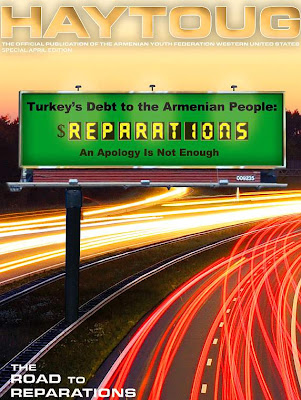

Following Articles From "Haytoug, April 2009 Issue" Published By The Armenian Youth Federation May Change Your Mind. .

- The Debt That’s Owed ( Message From The Editors (Armenian Youth Federation, Glendale, California USA)

- Securing Justice And Survival: An Interview With Dr. Levon Marashlian

- Justice, Dignity And Security: The Manifold Reasons Why Reparations Are Necessary by Serouj Aprahamian

- Insurance Reparations By Ani Nalbandian

- A Case For Reparations For The Armenian Genocide By Vaché Thomassian

- What Is In Our Best Interest: Yerevan And The Genocide, By William A. Bairamian

The Debt That’s Owed ( Message From The Editors (Armenian Youth Federation, Glendale, California USA)

It can be said that the struggle for the Armenian Cause which was reinvigorated in the second half of the 20th century was truly one of the most remarkable grassroots political movements to develop internationally. The fruit born of this movement can be witnessed today in the countless national, municipal and local assembly’s around the world that have officially acknowledged the Genocide; the vast body of scholarly documentation and academic consensus on the matter; the socially conscious musical and cultural expressions associated with the Cause; the rejection of denial and adoption of editorial policies among media outlets recognizing the facts of the Genocide; and the countless educational and political events which take place in community’s every year on April 24 and beyond.

That Armenians have succeeded in shaking the indifference of the world and moved beyond the once necessary task of proving historic facts is beyond doubt. Even in Turkey, we see the tide of awareness generated by the movement rapidly eroding the wall of denial erected by Ankara. These realities suggest to us that the movement for justice for the Armenian Genocide has reached a turning point; the time has come to raise the bar on our actions and aims beyond just recognition.

Concurrent with the need for upholding historic truth, there is a need to finally begin holding Turkey accountable for the massive debt it owes to the Armenian nation.

Although nothing can ever make up for the suffering, loss, trauma, robbery, and destruction inflicted onto the Armenian people—f rom the Ot toman Turkish government’s genocidal intent, to the culpability of the Republic of Turkey for continuing prejudicial policies and a full blown denial campaign—the need for some sort of meaningful atonement and restitution is indisputable. Those who think that there could ever be a genuine reconciliation between Armenians and Turks without the latter attempting to restore the dignity, property, wealth, self-determination, and cultural heritage of the Armenian people are truly fooling themselves.

How exactly this debt will ultimately be paid is not something we can fully address or predict here. Moving forward effectively will take more expertise and serious planning than we can offer in these few pages. What we can do, however, is sound the call for our entire community to steadily broaden its focus beyond just recognition.

The time is long past due to begin initiating strategies, initiatives and campaigns centered on attaining reparations and restitution for all that was taken from us during the Genocide.

Although the road has been long and winding, the message has always remained crystal clear—A hollow apology will not suffice in bringing justice to the Armenian nation.

Securing Justice And Survival: An Interview With Dr. Levon Marashlian

Levon Marashlian is a Professor of History at Glendale Community College, teaching Armenian history and Diaspora current affairs. In 1996, he testified before the US House of Representatives during a hearing on the Armenian Genocide and has also testified in favor of legislation mandating the teaching of the Armenian Genocide in secondary schools. He is the author of numerous publications, articles, and letters to the editor in scholarly journals and the general press regarding the Genocide. He is also a frequent commentator on such matters in the US and Armenian media. In addition to the killings and massacres, you’ve written extensively about the Turkish government’s systematic effort to rob Armenians of their wealth and possessions during the Genocide.

What would you say to those who argue that the modern Republic of Turkey bears no responsibility for these crimes since they were committed under the Ottoman Empire?

There are ethical and legal dimensions to this question. Legally, there’s a statute of limitations for most crimes. At some point, you can no longer try to get justice. But when the crime is genocide, it opens up the possibility of negating statute of limitation laws. That may be one of the reasons why the word genocide is so important for Turkey. I can’t speak about the legal aspect in detail; you need a lawyer for that.

The ethical, or moral aspect is related to the legal aspect and it involves a new government’s responsibility for the liabilities of the previous government. One argument is that today’s Turkish Republic is not responsible for the actions of yesterday’s Ottoman Empire. Yet today’s Republic benefits from the assets of the previous Empire.

So a counterargument is that if a new regime acquires the wealth accumulated by the previous regime, then it should also accept the liabilities of the previous regime. In fact, this question of a transfer of liabilities is sometimes written in treaties. If there’s a continuity of benefit, there should be a continuity of responsibility.

You mentioned the ethical and legal aspects. In the past, you’ve also discussed the importance of reparations in terms of survival and security for the Armenian Republic. Can you talk to us about that and explain how justice for the Genocide can help ensure Armenia’s viability?

It seems that more and more people seem to think that an apology from Turkey is enough. And some people even think that Armenians devote too much attention to recognition. Their argument essentially goes like this: “Now we have a Republic and it is poor;

it has enormous problems. Spending all of this energy and money on Genocide recognition is hindering efforts to solve Armenia’s many problems and insisting on recognition is contributing to keeping the border closed. Therefore, while we should not forget the better improve conditions in Armenia.” So, for some people, the Genocide issue is an unnecessary burden for Armenia.

I disagree with this way of thinking. First, the Genocide is the main reason for Armenia being in the situation it is in. Of course corruption and incompetence on the part of Armenians are also reasons, but the human and material losses during the Genocide are the main factors. One of the purposes of the deportations and massacres was to make Armenians irrelevant in the region. If Armenia stays in its present situation, it can become increasingly weaker and more dependent on foreign aid. Eventually, it might become a country that is independent in name only, and there is even the potential danger of disappearing entirely.

That Armenia needs a huge influx of resources is undeniable. The aid and investments from the Diaspora and other sources are not enough. Without a huge addition of resources, my fear is that Armenia doesn’t have a very bright future. It can be argued that its very existence is threatened, and that the situation is mainly a consequence of Turkish policies from 1915 to 1923.

And resolving the Genocide issue in a just way may be Armenia’s only hope for survival as a viable and prosperous state. Therefore, rather than being an unnecessary burden, justice for the Genocide issue may be Armenia’s only salvation from the situation it finds itself in as a consequence, primarily, of Turkish policies.

What are your thoughts regarding the applicability of the Treaty of Serves today, since many people have that on their minds when they think of Armenia’s legal and national claims against Turkey?

The Treaty of Sevres has a very important value.

Whether it’s legally valid or not today, you would have to ask international lawyers. But even if it is not legally valid, it still has a very important moral validity because it reflects the opinion of the world community in general—not just the opinion of Armenians, but the opinion of Britain, France, Italy, Japan, the US, and other countries, and signed by the Ottoman government).

Sevres defined what justice for the Armenian people was in the opinion of the most powerful countries of the time, and those countries exist today.

The Treaty of Sevres still attracts a lot of attention in Turkey today. If didn’t mean anything, then Turkey would not have what is called the “Sevres Syndrome,” which comes to the surface especially around August 10, the day it was signed in 1920.

I should mention here that the “Sevres Syndrome” is not just about Armenia, but about Kurdistan and other issues too. So it opens up a lot of issues for Turkey.

Now obviously, Armenians have to be realistic. They cannot now imagine they could get everything in the Treaty of Sevres. That’s unrealistic. But my feeling is that Turkey does owe something to the Armenian people, and that it is relevant to Armenia’s survival.

What are the incentives, if any, for the Turkish government and people to come to grips with the crimes committed against Armenians and take the necessary steps to provide restitution?

Obviously most Turks react to this issue with hostility. If the Turkish government does not want to admit to the Genocide for moral reasons, it’s not going to want to talk about material justice. Nevertheless, I feel that Turkey itself would benefit from a just settlement of the issue. Let’s just imagine that Turkey acknowledges the Genocide and arrives at an equitable settlement. That would make them look great. It would give them greater prestige. Their image would soar in the world.

Turkey can learn from Germany. Because they’ve acknowledged the Holocaust and paid reparations, there aren’t Jewish resolutions against Germany every year or demonstrations at German consulates. The Germans can hold their heads up high.

Today’s Turks, on the other hand, even though they obviously are not personally guilty of massacre and plunder, have this burden that they’re still carrying because of their government’s policy of denial. They have this albatross around their necks. And it’s rotten. By getting rid of it, they would cleanse their conscience and gain international respect. And Armenia would have a better chance to survive as a viable and friendly neighbor.

Justice, Dignity And Security: The Manifold Reasons Why Reparations Are Necessary by Serouj Aprahamian

When it comes to discussion of the Armenian Genocide, there is one topic that has, for far too long, been the proverbial “elephant in the room.” Although the topic is on virtually everyone’s mind, it tends to be left largely unaddressed or ignored for one reason or another. This topic is, of course, that of reparations.

For some, the idea of reparations is a radical “dream”; an impossible and fanatic proposition which takes away from the more feasible task of achieving recognition.

It is taken for granted that the most Armenians can reasonably hope for is acknowledgment and an apology from Turkey.

Among many such individuals, the cause of reparations is looked upon with automatic disapproval and disdain. Hence, the topic itself is barred from any serious consideration. On the other side of the spectrum, there are those who maintain that recognition without reparation is meaningless; that the Turkish government must pay for the crimes it has committed and not be allowed to walk away scotfree.

In this case, also, we find many who consider the matter so straightforward, that they see no need in discussing it further or elaborating upon the reasons why reparations are so fundamentally needed.

We argue that, not only are reparations far from being an unreachable goal, they are the only practical means for effectively bringing the Genocide issue to any sort of a just resolution. Given its crucial importance to healing the wounds created by the Genocide, it is imperative that the merits and meaning of reparations be properly explained and expounded upon. This article will attempt to lay out some of the many reasons why reparations are so essential.

Justice At The Core Of Why Reparations are necessary is the concept of justice. A colossal crime was committed against the Armenian nation and our moral instinct demands that we redress this in an adequate fashion. This major wrongdoing must be compensated for in order to restore some semblance of balance and normality.

To illustrate, let us imagine for a moment that someone tortures, rapes, and murders your family; invades and occupies your home; steals all of your wealth and belongings; desecrates your family heritage and possessions; and expels you by force from your home.

Not only does the perpetrator refuse to give any compensation to your family, he aggressively denies that a crime ever even took place. The blame is deflected, instead, upon you and your offspring—who must struggle to even mourn or remember their family—while the criminal portrays himself in public as the victim.

After all of this, would it be enough for the criminal to simply give you an apology and say he will no longer inflict any further mistreatment on you? Of course not!

It would be perfectly reasonable for all of us to want some sort of reparations; some form of payment for the damage that has been done.

In this vein, the Turkish government has a moral responsibility to pay the huge debt it owes to the Armenian people. Just because Turkey has, as of yet, not paid this debt does not mean that the debt itself disappears. On the contrary, it is the Armenian people who are continuing to bear the brunt of this debt through the loss of years of human and material capital, dispersion in the Diaspora, the compromise of our historic homeland, a small and landlocked Republic, psychological suffering, and economic hardship.

Indeed, a great deal is already being paid—the problem is that it is largely the victim rather than the perpetrator who is doing the paying.

For this reason alone, some form of reparations proportionate to the suffering caused by the crime is a must for anyone concerned with upholding justice and repairing the wounds wrought by the Genocide. As explained by genocide scholar Taner Akcam in a recent commentary about discussions of the Genocide within Turkey, “The process of healing a past injustice must take place within the realm of justice, not [just] freedom. . . Today, however, in many democratic nations in the West .

. . Injustices of the past are freely discussed, but the wounds from the past continue because justice remains undone. All of the power ful states’ relationships with former colonies; the massacres and genocidal episodes from colonial periods; slavery in America, etc., all of these remain unresolved in the realm of justice. Therefore, even if the ‘Armenian problem’ were to be discussed freely in Turkey it would nevertheless remain unresolved.”

Dignity Closely related to the issue of justice is the maintenance of human dignity for the Armenian people.

It is well known that one of the principal features of genocide is the denigration of the target population’s humanity. Once again, as Akcam points out:

“Every large-scale massacre begins by removing the targeted group from humanity. That group’s human dignity is trampled on, and they begin to be defined by biological terms like ‘bacteria,’ ‘parasite,’ ‘germ,’ or ‘cancerous cell.’ The victims aren’t usually defined only as something that needs to be removed from a healthy body: they are socially and culturally demeaned, their humanity removed. . . Our humane duty is to restore the dignity of these victims and show them the respect they deserved as human beings.

Reparations and other similar moves to heal past injustice work to restore the victims’ dignity and gain meaning as a way of repairing emotional wounds.”

To ask that the Turkish government merely grant us an apology without demanding that they do anything significant to rectify our suffering—or worse, to seek “reconciliation” without addressing the Genocide at all—is the ultimate form of surrendering our human dignity. Giving up our rightful claims and simply seeking to have the perpetrator acknowledge what we already know to be true is equivalent to forfeiting our rights as a people; and, hence, indirectly accepting the success of the Genocide itself.

Pursuing such an outcome will prove to be even more detrimental to the dignity, self-respect, and self-determination of the Armenian people than not having the Genocide recognized at all.

Security Finally, the matter of reparations has profound meaning for the security and viability of the Armenian Republic.

Let us not forget that the motivation behind the Genocide itself was to destroy Armenians as an entity in the region.

The present borders of Armenia were purposely designed under pressure from Turkey as a way of reducing the country into one incapable of surviving on its own.

Such a policy of aggression was fueled by an institutionalized prejudice against Armenian national self-determination which continues to manifest itself in Turkish society to this day.

Changing this reality will require more than a mere symbolic apology or recognition of historical facts. It will require meaningful compensation and tangible measures which ensure Armenia’s long-term sustainability, as well as programs to tackle the hostile attitudes in Turkish society against its neighbors and minorities.

As scholar Henry Theriault has pointed out, recognition alone is no guarantee of improved relations or a change in Turkey’s adversarial stance. Indeed, Ankara could stand up tomorrow and admit the historical reality of the Armenian Genocide, only to retract its statement or worsen relations the day after. In his words, “The giving of reparations, especially land reparations, transforms acknowledgment and apology into concrete, meaningful acts rather than mere rhetoric.”

In addition, reparations are an important deterrent for future governments in Turkey—and potential perpetrators of genocide around the world—from repeating similar atrocities in the future.

Failure to implement any sort of punishment for an act as horrific as genocide sends a signal to despots everywhere that they can commit such acts with impunity. This is certainly the lesson Turkish leaders have drawn as they have gone on to suppress and carry out massive ethnic cleansing operations against their own Kurdish minority.

As Armenians, we have a moral responsibility to prevent future atrocities and end the cycle of genocide. To give up our demands for reparations and simply seek an apology for the Genocide would be worst than not having it recognized at all. This is because we would be helping Turkey tell the world that a state can commit genocide, admit to it, and subsequently face no consequences whatsoever.

Resolution through Reparations For these, and a host of other reasons, it seems clear that a lasting solution to the pain, loss, and enmity created by the Armenian Genocide will necessarily require large-scale reparations on behalf of the Turkish government. Otherwise, any hope of genuine reconciliation and regional stability will remain a hollow illusion.

To those who would still argue that, despite the merits, forcing reparations from Turkey is a hopeless and impossible dream, we would remind them that a mere twenty years ago, the same would have been said about those seeking the independence of Armenia.

It would have been equally “unrealistic” to imagine then that a Turkish Nobel laureate and countless dissident intellectuals would be openly questioning Ankara’s narrative on the Armenian Genocide.

Today, the world is more aware than it has ever been about the facts of the Armenian Genocide, and we see the Turkish government increasingly on the defensive when it comes to this issue.

The momentum towards moving beyond recognition and securing compensation for the countless losses incurred during the Genocide is also increasingly gathering pace. Thus, rather than being an impossible dream, the attainment of reparations appears, in many ways, the most probable in recent memory.

Furthermore, as we have shown, seeking recognition without reparation is potentially more harmful than not attaining recognition at all. As such, achieving reparations remains the most critical means for securing a just and lasting resolution. Concurrently, to turn away from reparations would be a disservice to all those who have suffered from the Genocide and those who continue to struggle to overcome it.

Insurance Reparations By Ani Nalbandian

We all know about the atrocities that occurred during 1915-1923. What we do not know is what happened to all the money and property the victims of the Armenian Genocide lost.

Throughout the years following 1915, the victims and their families were not necessarily worried about acquiring their lost wealth but more of escaping the memories of the slaughter of their loved ones along with the trauma of being exiled from their homeland.

However, one woman, Yegsa Marootian, was brave enough to stand up and claim her lost assets.

Upon arriving to New York in 1920, Yegsa went to the New York Life insurance company and filed a claim as the beneficiary of her murdered brother’s insurance policy. Unfortunately, she was turned down because she could not provide a death certificate and because the statute of limitations on her claim had run out. She was denied and offered zero compensation.

Seventy-nine years later, Martin Marootian, Yegsa’s son, sued New York Life along with dozens of other plaintiffs for not giving the insurance claims of the Genocide victims who fell in 1915. They demanded the list of Armenian life insurance policy holders and compensation by New York Life to the heirs. Once this lawsuit began to garner attention, Adam Schiff along with 13 other cosponsors introduced H.R. 3323: The Armenian Victims Insurance Fairness Act. This Act was to “permit States to require insurance companies to disclose insurance information.”

Though the bill never became law it did make a point to the insurance companies to compensate these victims and their families for their claims.

After years of negotiations the lawsuit was finally settled. New York Life was to give $20,000,000 in insurance reparations to the beneficiaries; $4,000,000 would go to the lawyers and $3,000,000 would go to various Armenian social service agencies.

Even though New York Life has given the money they owed to the Genocide victims and their beneficiaries, there are still many other banks and insurance companies who owe these victims their lost wealth and fortunes. Following the New York Life case, the firms in the forefront of the insurance lawsuit—Kabateck Brown Kellner LLP, Geragos & Geragos, and Vartkes Yeghiayan & Associates—filed and won a similar $17 million settlement from AXA for unpaid life insurance benefits.

They currently have several other lawsuits pending against companies who usurped assets from the Genocide.

These victories demonstrate the value of pursuing justice through the court system and being vigilant, not just against Turkey, but all those who reaped benefits from the victims of the Armenian Genocide. They have proven in concrete terms that there are other avenues for justice parallel to and beyond the important task of gaining Genocide recognition.

*Editor’s note: Although the New York Life lawsuit resulted in a positive settlement, much more research is needed in the realm of quantifying genocide-era losses—be they life, property, or territory in order to reach proper settlement.

A Case For Reparations For The Armenian Genocide By Vaché Thomassian

Today we live in an age where there is an expanding sense of global awareness; consequently there has been a rise in the legal demands to repair what has been damaged in the past and to press nations to come to terms with their oft brutal histories. This relates to the idea that law is an instrument of the entire society not simply one nation or group. Nowadays, if a people are injured there is a burden on the international community not only to stop the injury and prevent future harm, but also to assist the healing process, by holding the guilty accountable for their crimes, in order to restore a balance of justice.

This relatively newfound understanding for victim’s rights has led to the spawning of reparations politics; in order to confront historical injustices and properly address them.

I. Reparations: Theoretical Foundations and Goals The value in compensating historic injustices lies with its ability to reinstate a sense of dignity to the victim group and descendants of the victims, while simultaneously compelling the perpetrator or beneficiary group to recognize the harm caused. It is important to make a distinction here between the notion of restitution and repa rations. Restitution attempts to make whole the physical losses of a crime, while reparations seek to make up for lost opportunities as well as address the psychological impact of the harm committed. It can be said that reparations are both backward-looking and forward-looking because they seek to assess and compensate past injustice, while attempting to better the future lives of the victim group.

Theoretical foundations for reparations can be seen in many classical writings. In his Second Treatise of Government, John Locke states that man has a “particular right to seek reparation from him that has done it [committed an injury]:

and any other person, who finds it just, may also join with him that is injured, and assist him in recovering from the offender so much as may make satisfaction for the harm he has suffered.” This shows the idea of the community joining to repair damage by making the responsible party accountable.

The goal or aim of a system of reparations must be broader than simply punishing the perpetrators of a crime. A system of reparations must serve to first identify an injustice that has occurred. Next, it must objectively bring the issue out to the open to be discussed without any deception or concealment. Consequently it must seek redress for the victim-group in a just manner.

These steps must be taken in order for there to be a chance of proper reconciliation down the road.

II. Comparative Instances of Reparations: The German-Japanese Pendulum The varying spectrum of outcomes possible from reparations movements can be described as the German-Japanese Pendulum. On one end of the pendulum there is a model for reparations provided by the aftermath of the Jewish Holocaust. This has “emerged as a kind of ‘gold standard’ against which to judge other cases of injustice”.

Even before the end of World War II, Jewish organizations began discussing means of assistance to victims of Nazism as well as the fate of the Genocide-victims’ assets.

The War Emergency Conference of 1944, held by the World Jewish Congress, demanded “restitution of individual assets, the payment of compensatory indemnification and collective reparations to the Jewish people”. After the war, the Conference on Jewish Material Claims against Germany (Claims Conference) was convened to compensate the Jewish victims and to redress stolen or destroyed property. As a result of this Conference the West German Federal Indemnification Law was passed in 1952. This led to payments of over DM 100 billion (over $65 billion) along with countless community building and assistance programs to aid victims of Nazi oppression. In this case, the post-war German government accepted their wrongdoing and instituted reparations and programs to make amends.

On the opposite side of the pendulum there is an instance of strong reluctance to address past inequities; the case of the, euphemistically described, “Comfort women” who were forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military during the Second World War. These women, mostly of Korean decent, have struggled unsuccessfully for years to get a formal apology from the Japanese government. So far, the government’s way of dealing with this historic injustice has been to avoid direct governmental acknowledgment; using nongovernmental means to “purchase” atonement for the crime. This impersonal method of approaching the issue has caused many of the victims to reject the “blood money”; demanding the reparations be paid directly from the government as a symbolic gesture. Other historical instances which are now being revisited include, New Zealand, which expropriated the land of the native Maori tribe and the United States which is confronted with the task of addressing the Genocide of the Native Americans as well as the ramifications of over 200 years of African enslavement. Unfortunately, history has shown that it is usually political interests and conveniences that judge which side of the German-Japanese pendulum a reparations demand ends up, rather than it’s foundations in justice.

III. Overcoming Complexities: Reparations for the Armenian Genocide

Genocide is not an ordinary crime subject to periods of statutory limitation for purposes of prosecution. Pursuant to the United Nations Convention on the Nonapplicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity, no statute of limitations applies to the crime of genocide. Moreover, the International Criminal Court defines genocide as an offense erga omnes, an offense which is subject to prosecution, even if the victims are a State’s own population. Furthermore, among international lawyers there is consensus that the punishment of genocide must have a retroactive effect.

Turning to discussion of the Armenian Genocide, it can be said that initially hopes were high that the crimes against the Armenians would be met with prosecution, condemnation and punishment. These aspirations, however, soon evaporated as the post-World War I political climate shifted.

Nevertheless, the burden for recompensing Turkey’s national wrongdoings still rests with the government and population of the Republic; not simply due to the benefit individuals may or may not have received from the deportation and murder of the Armenians, but due to the fact that they (as a nation) are the successor to a genocidal regime. More than the tragic loss of over 1.5 million victims, the destruction of the Armenian homeland in Eastern Anatolia, the survivors had to emigrate and their children and grandchildren gradually and irreparably lost part of their culture and language--i.e. their identity. There is also the aspect of cultural genocide—monasteries, churches and other monuments attesting to the cultural heritage of the Armenians of Anatolia have been destroyed or purposefully allowed to decay. In the case of the hundreds of Armenian monasteries and thousands Armenian churches in Anatolia, the Turkish government should be persuaded by the European Union and NATO to return as many as were not destroyed and still exist, transformed into mosques, museums, prisons, sport centers, etc. to the Armenian Patriarch at Istanbul. The Turkish government should also be persuaded to finance the reconstruction of other Armenian historical buildings. From a corrective justice perspective it can be argued that the aim should be to put people back into the state they would have been in, had the injustice not taken place; in the Armenian case this would mean arguing that the benefits conferred to Turkey, as a result of the Genocide, alone justify the need for reparation.

The Treaty of Sèvres, of 1920, was the first treaty signed between the Allied powers and the Ottoman Empire. This landmark peace treaty aimed to, among other goals, correct the wrongs done to the Armenian people. It formally recognized Armenia as a sovereign, independent state, including the provinces of Erzerum, Bitlis, Van and Trebizond.

Unfortunately, for varying reasons the Treaty of Sèvres was not ratified by its signatories. The Treaty of Lausanne, which makes no reference to the Treaty of Sèvres or Armenia, was signed in 1923. It can be argued by historians and international law scholars whether the Treaty of Lausanne replaced or was an addendum to the Treaty of Sèvres, but the moral responsibility remains unchanged.

The homeland of Armenians for over 3000 years was expropriated with no remorse or regard.

This loss to the Armenian people has resulted in a loss of identity, culture and heritage; one that no monetary figure could replace. Every Armenian has Genocide-era stories and family accounts that describe the family home, beautiful land, churches, fruits that could grow like-nowhere-else and of course Mount Ararat, the national symbol of all Armenians since the time of Noah; along with the memories, there is a genuine desire to return home.

As long as the descendants of Genocide perpetrators continue to control lands that were acquired through Genocide, there is a certain sense of inferred consent to the acts which took the lands in the first place. As scholar Henry Theriault stated, “While it has become fashionable for the progeny of perpetrators to express their regrets over past abuses, the engagement with the past ends there”. For the current Turkish population and government to ignore the fact that part of their Republic was built on historically Armenian land, and to ignore their claims for justice is tantamount to acquiescence to the ideologies of the Young Turks.

Looking at the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide— which both Turkey and Armenia are signatories to—one can apply the general principle pacta sunt servanda which would require Turkey not only to refrain from committing genocide in the future but also implies that the victims of earlier genocides should be granted adequate reparations.

IV. Conclusion

There is abundant historical and archival evidence available worldwide to prove that Genocide was committed purposefully planned and executed by the Ottoman Empire against the Armenian people in 1915. This event lead to the deaths of over 1.5 million people, the deportation of the remaining Armenian population of Eastern Anatolia and the expropriation of land, property and assets. The original intent of these machinations continues to this day with the incessant campaign of Genocide denial set forth by the current Turkish government.

The righteous efforts of the international community to address the crimes through the Treaty of Sèvres were frustrated by political bargaining, but the desire for justice remains. Since the Turkish government, both past and present, has made no effort to ameliorate the injustices caused to the Armenian Nation, evidenced by its continual denial of the Armenian Genocide and the persistent maltreatment of the ethnically Armenian minority of Turkey today, the humanity of the Armenian people has been and continues to be violated.

The proper way in which this injustice must be resolved is through first acknowledging the crimes of the past and subsequently pressing for national affirmation of the need for reparations.

There is an international moral obligation to make amends for crimes such as genocide, and a political imperative for the international community to remove sources of tension, in order to create equal footing for a lasting reconciliation.

Although the Armenians can legitimately invoke many treaties and general provisions of international law to support their claims, political reality is such that progress often cannot be achieved by legal means alone. Even a judgment of the International Court of Justice is of limited value as long as it is not enforced. Enforcement of international law, including international case law, depends on political will.

Therefore, emphasis must be placed in creating the conditions that will reinforce a political will to do justice to the Armenian people.

What Is In Our Best Interest: Yerevan And The Genocide, By William A. Bairamian

Since its independence, Armenia has seldom had the time or the opportunity to dabble in international politics. The extent to which it has been involved has had to do primarily with the war for the independence of Artsakh and, its dealings with France, Russia, and the United States in establishing the terms for a definitive end to the conflict. Otherwise, Armenia’s involvement within the international framework has been limited to cooperation with European standards of governance, attempts at Western-oriented societal and legal refinements, and activities within the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

President Serzh Sarkissian strongly deviated from this posture when he invited Turkey’s president, Abdullah Gul, to Armenia, to watch a World Cup qualifying soccer match between the two countries. It was an active diplomatic effort that gained the praise of some and the disapprobation of others.

More importantly, it came with an implicit assertion: that Armenia was now willing to undertake greater objectives with regard to its foreign policy.

Heretofore, Armenianrelated issues were largely within the purview of Diaspora communities in their adopted countries around the world. From Armenian Genocide recognition to economic and military aid for Armenia to Artsakh’s right to self-determination, Diasporan organizations – like the Armenian National Committee - became adept at fighting for causes that affected not only the Armenians in their own communities but Armenians throughout the world. Expectedly, the Diaspora has become an indispensable part of foreign policymaking that affects Armenia. Noting this, among other considerations, a Ministry of the Diaspora was established, also under President Sarkissian’s administration. This was an important step in fortifying the established goals of the both the Republic of Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora.

Concerning one of these points in particular – the Armenian Genocide -, Yerevan should be conscious of the much larger role it can play than it already has.

The stated policy of the Republic is that it demands the recognition of the Genocide by Turkey. As a country in the international system, Armenia is part of apparatuses that allow it to bring forth the Armenian Genocide issue in myriad arenas. For example, it is wholly capable of vigorously objecting the Turkish government’s attempts to silence any discussion about the Genocide within the United Nations. As a member of the UN, the freedom to express itself is Armenia’s right – one that Turkey has no qualms about using – and one that Armenia should feel similarly, and unabashedly, comfortable with.

Further, it is incumbent upon Armenia to actively demand that Turkey recognize the Armenian Genocide.

This may seem as a simple enough gesture but one that it seems the government in Yerevan has shied away from in the face of diplomatic concerns. The reality is that Turkey closed its border with Armenia 16 years ago for no reason other than an apparent attempt to suffocate its neighbor to the east and make it doubly difficult for its citizens to survive. Unsurprisingly, Armenians once again withstood a vile test of their tenacity and have progressed significantly while eastern Turkey remains a derelict landmass, ignored even by its own government. Thus, when Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan puts preconditions on the amelioration of relations with the Armenian government – such as dropping the pursuit of recognition, reparations, and restitution – Yerevan must respond with equal force and publicly reaffirm its conviction to attain justice for the 1.5 million Armenians who were slaughtered at the hands of Ottoman Turks.

In reemphasizing its efforts, the Armenian government can utilize the newly established Ministry of the Diaspora to communicate and coordinate with those who understand, through decades of experience, the foreign governments Armenia is now dealing with.

Likewise, Armenia’s vocal support of Diasporan endeavors in foreign countries would undoubtedly be a boon to those activities. It ought to also be willing to explain the reasoning behind overtures such as those made to Turkey, which have yet to become elucidated by any government official. In that vein, Armenia should emphasize to PM Erdogan that fully normalized relations will be impossible until Turkey acknowledges the truths of its history and remedies the injustices that befell the Armenians in Anatolia as they experienced one of the worst horrors of human history.

There is no place for timidity in world politics and the decades-long struggle of the Diaspora must now be met with commensurate zeal on the part of the independent Republic of Armenia. Having weathered a war, an earthquake, and closed borders for much of its existence, the Third Republic must be supremely confident of its ability to manage complex situations.

It cannot and must not be afraid to assert itself on the world stage and it must swiftly respond to the purposeful falsification of its history with vigor. Succinctly, Armenia must be forward, frank, and fastidious in its pursuit of justice for the victims and survivors of the Armenian Genocide at every juncture – it is, indeed, its duty.

Armenians Demanded “Recognition, Reparations, Restitution” During The Armenia V. Turkey Soccer Match In September 2008.

South American Parliamentarians Coalition Resolution November 19, 2007 • Chile Senate Resolution June 5, 2007 • Chile Senate Resolution June 5, 2007 • Argentina Law January 15, 2007 • Argentina Senate Special Statement April 19, 2006 • Lithuania Assembly Resolution December 15, 2005 • European Parliament Resolution September 28, 2005 • Venezuela National Assembly Resolution July 14, 2005 • Germany Parliament Resolution June 15, 2005 • Argentina Senate Resolution April 20, 2005 • Poland Parliament Resolution April 19, 2005 • Netherlands Parliament Resolution December 21, 2004 • Slovakia Resolution November 30, 2004 • Canada House of Commons Resolution April 21, 2004 • Argentina Senate Declaration March 31, 2004 • Uruguay Law March 26, 2004 • Argentina Law March 18, 2004 • Switzerland (Helvetic Confederation) National Council Resolution December 16, 2003 • Argentina Senate Resolution August 20, 2003 • Canada Senate Resolution June 13, 2002 • European Parliament Resolution February 28, 2002 • Common Declaration of His Holiness John Paul II and His Holiness Karekin II at Holy Etchmiadzin, Republic of Armenia September 27, 2001 • Prayer of John Paul II Memorial of Tzitzernagaberd September 26, 2001 • Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly Resolution April 24, 2001 • France Law January 29, 2001 • Italy Chamber of Deputies Resolution November 16, 2000 • European Parliament Resolution November 15, 2000 • Vatican City Communiqué November 10, 2000 • France Senate Law November 7, 2000 • Lebanon Parliament Resolution May 11, 2000 • Sweden Parliament Report March 29, 2000 • France National Assembly Law May 28, 1998 • Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly Resolution April 24, 1998 • Belgium Senate Resolution March 26, 1998 • Lebanon Chamber of Deputies Resolution April 3, 1997 • U.S. House of Representatives Resolution 3540 June 11, 1996 • Greece (Hellenic Republic) Parliament Resolution April 25, 1996 • Canada House of Commons Resolution April 23, 1996 • Russia Duma Resolution April 14, 1995 • Argentina Senate Resolution May 5, 1993 • European Parliament Resolution June 18, 1987 • U.S. House of Representatives Joint Resolution 247 September 12, 1984 • Cyprus House of Representatives Resolution April 29, 1982 • U.S. House of Representatives Joint Resolution 148 April 9, 1975 • Uruguay Senate and House of Representatives Resolution April 20, 1965 • U.S. Senate Resolution 359 May 11, 1920 • U.S. Congress Act to Incorporate Near East Relief August 6, 1919 • U.S. Senate Concurrent Resolution 12 February 9, 1916 • France, Great Britain and Russia Joint Declaration May 24, 1915 • United Nations Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities July 2, 1985 • International Court of Justice May 28, 1951 • United Nations War Crimes Commission Report May 28, 1948 • United Nations General Assembly Resolution December 11, 1946 • Verdict (“Kararname”) of the Turkish Military Tribunal July 5, 1919 • Indictment of the Turkish Military Tribunal 1919 • Treaty of Sèvres August 10, 1920 • Stephen Harper, Prime Minister of Canada April 19, 2006 • Jean Chrétien, Prime Minister of Canada April 24, 2002 • Konstantinos Stefanopoulos, Official recognition of the Armenian Genocide by the innumerable scholars as well as the Parliaments and leaders of countless nations should inspire the Republic of Turkey to recognize its historical responsibility and to provide a measure of reparation to the descendants of the survivors of the genocide. President of Greece July 10, 1996 • Jean Chrétien, Prime Minister of Canada April 24, 1996 • François Mitterrand, President of France January 6, 1984 • Al-Husayn Ibn ‘Ali, Sharif of Mecca 1917• South Australia State Legislative Council March 25, 2009• Province of Cordoba Legislature September 6, 2006 • Province of Buenos Aires Parliament June 15, 2006• Legislative Assembly of British Columbia April 3, 2006• Legislature of Ontario, Canada March 27, 1980• National Assembly of Quebec April 20, 2004• Il Consiglio Provinciale di Roma June 16, 2000• Republic and Canton of Geneva Declaration December 10, 2001• Canton of Vaud (Etat de Vaud) September 23, 2003• Wales National Assembly Resolution, EDM 1454 January 24, 2006• Alaska State Senate April 23, 1990 • Alaska State Governor April 19,1990 • Arizona State Governor April 23, 1990 • Arkansas Executive Department Proclamation March 27, 2001 • California State Governor April 7, 2008 • California Senate Joint Resolution April 10, 2003• California Assembly Joint Resolution April 26, 2002• California State Legislature May 11, 2000• Colorado Senate Joint Resolution April 24, 2008 • Colorado State House Joint Resolution April 16, 2004 • Colorado State Governor March 14, 1990 • Connecticut Governor’s Proclamation April 24, 2001 • Delaware Senate Concurrent Resolution April 11, 1995 • Florida State Governor April 27, 1990 • Georgia State Senate February 8, 1999 • Hawaii House of Representatives April 6, 2009 • Idaho, Governor, Proclamation April 20, 2004 • Illinois State Governor March 11, 2005 • Illinois State House of Representatives April 24, 1997 • Illinois State Senate April 5, 1990 • Kansas State Governor April 20, 2005 • Kentucky State Governor April 28, 2008 • Louisiana State Governor April 18, 2004 • Maine Joint Resolution June 13, 2001 • Maine State Legislature April 7, 2000 • Maryland House Resolution May 18, 2001 • Maryland Senate Resolution March 26, 2001 • Maryland State Governor April 24, 1990 • Massachusetts General Court April 13, 2006 • The Commonwealth of Massachusetts March 23, 1990 • Michigan State Senate August 28, 2002 • Michigan State Legislation April 26, 2001 • Michigan House Joint Resolution April 19, 2001 • Michigan State House of Representatives April 22, 1999 • Michigan State Governor April 16, 1990 • Minnesota State Governor April 20, 2005 • Missouri State House Concurrent Resolution May 8, 2002 • Letter from the Governor of Montana 2004 • Nebraska State Governor April 23, 2004 • Nevada State Governor April 11, 2000 • New Hampshire State Governor April 22, 2005 • New Hampshire State Senate April 24, 1990 • New Jersey State Governor April 18, 2006 • New Jersey Joint Resolution May 5, 2005 • New Jersey State General Assembly April 5, 1990 • New Mexico State Governor April 24, 2006 • New Mexico State Senate March 10, 2001 • New York State Governor April 19, 2006 • New York State Legislature April 19, 2002 • New York State Senate May 6, 1986 • New York State Assembly • North Dakota House Concurrent Resolution January 3, 2007 • Ohio Governor Proclomation April 17, 2007 • Oklahoma State Legislature March 26, 1990 • Oregon State Governor April 23, 1990 • Pennsylvania House Resolution March 28, 2005 • Rhode Island House Resolution April 24, 2008 • Rhode Island Senate Resolution April 24, 2008 • South Carolina House Concurrent Resolution April 24, 1999 • Governor’s Day of Recognition Certificate April 23, 2004 • Texas House Resolution April 24, 2006 • Utah, Governor, Proclamation 2001 • Vermont Governor April 24, 2004 • Virginia Governor April 24, 2001 • The General Assembly of Virginia March 9, 2000 • Washington State Governor April 20, 1990 • State of Wisconsin Senate February 20, 2002 • Wisconsin State Assembly May 2, 2000 • Wisconsin State Governor April 24, 1990 • Wisconsin State Legislature January 30, 1990 • The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity April 9, 2007 • Human Rights Association of Turkey, Istanbul Branch April 24, 2006 • European Alliance of YMCAs July 20, 2002 • Le Ligue des Droits de l’Homme May 16, 1998 • The Association of Genocide Scholars June 13, 1997 • Parlamenta Kurdistanê Li Derveyî Welat April 24, 1996 • Union of American Hebrew Congregations No-. .

Source APRIL 2009 HAYTOUG

Armenian Youth Federation .

5 comments:

All these people live in a dreamland and treasure of John Silver by getting some "reparations" or jackpot prize.

Got good news for American Armenians, they can lick their fingers, if they only wake up to REALITIES and READ OFFICIAL documents, such as: (# 2644)

Take a cold beer over your dreams for which you have been paying expecting a reward.

I am amazed at the "prejudiced readings and imaginations of those youngsters"! Take it easy and ask your elders, why they have not read and advised you!

Love to all

S.S. Aya

What about the reparations and the restitutions to Azerbaijan for the invasion, the occupation and the ethnic cleansing in the Karabakh, and also in seven other Azerbaijanese districts, still occupied by Armenian army?

Several thousands of Azeri civilians were massacred, around 800,000 were expelled, between 1991 and 1994. Almost 20 % of the Azerbaijanese territory is still occupied by Armenia.

S.S. Aya,

what official documents are you referring to?The only official document is the Treaty of Sevres that Turkey is currently ignoring.The treaty of Sevres can not be annuled by the treaty of Kars or the treaty of Moscow or the treaty of Laussane, because of the Arbitration Law . .

REPLY TO Anonymous "North Hollywood, California, United States Connect-to Communications (76.191.228.236)":

1. As much as the Soviet Russia cannot be responsible for the Csarist Russia Treaties (since they revolted and had they lost they would have been all killed), Mustafa Kemal being a "rebel , condemned by the Ottoman Empire to death", and his new REPUBLIC cannot be held accountable for a Treaty signed by an OVERTHROWN and EXILED Dynasty (instead of killing like Communists did). The REBEL NATIONALISTS had declared at that time that the Ottoman Government was no longer "representing Turkish People".

2. The Sevres Treaty "was not ratified by any of the signatories" (except Greece), let alone even the shaky Armenian Republic!

3. Four months after the Sevres Treaty and even before it reached Yerevan, the Armenian Democratic Republic surrendered on 2.12.1920 with Alexandropol Treaty to Nationalist New Rebel government and rennounced all past agreements. (Read the Treaty!) This Treaty was ratified by Yerevan

4. France, "one of the two great Enemy Countries", by signing the Ankara Treaty on 20.10.1921, themselves annuled and disregarded the Sevres as "waste paper"!

Did Tsarist Russia exist to sign it? Wasn't it one of the three great enemies? Sevres was a dead fetus!

Under current rules and laws, any party that can make any such claims officially, will only display it is own absolute naivety. The "Anonymous" and those "dreaming" may as well try to make a formal request, wherever, whenever they wish and see the reaction!

So, here we have it. It's about the money! The Treaty of Sevres was a dead letter from the start and even contradicted Wilson's 14 points (bad and illconceived as they were) which were supposed to have been the driver of post war settlements. Only the Armenians seem to live in the Sevres dream world.

Post a Comment

Please Update/Correct Any Of The

3700+ Posts by Leaving Your Comments Here

- - - YOUR OPINION Matters To Us - - -

We Promise To Publish Them Even If We May Not Share The Same View

Mind You,

You Would Not Be Allowed Such Freedom In Most Of The Other Sites At All.

You understand that the site content express the author's views, not necessarily those of the site. You also agree that you will not post any material which is false, hateful, threatening, invasive of a person’s privacy, or in violation of any law.

- Please READ the POST FIRST then enter YOUR comment in English by referring to the SPECIFIC POINTS in the post and DO preview your comment for proper grammar /spelling.

-Need to correct the one you have already sent?

please enter a -New Comment- We'll keep the latest version

- Spammers: Your comment will appear here only in your dreams

More . . :

http://armenians-1915.blogspot.com/2007/05/Submit-Your-Article.html

All the best