Introduction

Introduction Migration is a fact continuously experienced by communities. Nobody wants to desert his country unless he is compelled to do so. People’s affection towards the place they were born and grown is lifetime sentimental case. The yearning felt by those who left their homelands continues lifelong. The reasons of migrating to other places are not expected to be the reasons acceptable to others. Each migrant has his own justification.

The desire to migrate of the ancient world nations increasingly continued throughout the 19th century. The significant part of the migration was done to America that was trying to increase its population. Due to its vast geography and the need for manpower, and without considering the qualifications, America welcomed any migrant having no contagious disease. The Ottoman Empire’s disturbance with its subject who migrate to America and changed nationality and the fact that the America acted in a way of not caring the distress of the Ottoman Empire constituted the most important reason of the occasional tension in the relations between the two countries in the 19th century.

A. Reasons to Migrate . .

Due to the wars lasting centuries and the fact that they constituted the fighting sector of the population, Turks left all branches of the industry to non-Muslims. Armenians among the non-Muslim subjects improved themselves in this field and became dominant in stock broking, trade and industry. Since their feelings and traditions resembled very much to those of Turks as a result of the fact that they lived together in the same region, they adapted themselves to the Turks, gained their confidence and became the most influential of all subjects. At that time, it was hard to find to any senior official who is not indebted to Armenians. Even the poorest peasant owed them the cost of the seeds he sowed [1]

The Armenians who were living in the east of the Ottoman territories constituted the rich rank of the regional people [2]. Famous for it studies on Armenians, Vladimir Mayewsky wrote in his book that Armenians were engaged in any kinds of industrial branch and farming, and made social and psychological judgments. According to Mayewsky, Armenians are divided into two groups as the city-dwellers with unequal social status and the villagers. Their striking nature is that they have passion for passion, but that they make any effort for this. They are desirous to make fortune, against which is generally too hard to compete with. They are thrifty and have the ability to reduce the expenses to the minimum level. They are highly mean in spending for entertainment.

The city-dweller Armenians took the trade completely under control in the cities where the Greek Cypriots, who were in serious competition with them, did not exist. They gathered in cities especially for trade and art. Each Armenian with a mid-level of education was highly knowledgeable about the politics pursued in the country. Having fame, boasting oneself and only valuing their own idea always existed in their thoughts. The fact that their villagers had the art of farming and artificial irrigation suggests that they were in better conditions r than the then Russian villagers.

The Armenian clerics worked for developing the national thoughts instead of carrying out religious activities. These thoughts found the opportunity to germinate between the silent walls of the mysterious monasteries. In those places, Christian-Muslim religious feud were settled rather than religious rites. Schools and the Church schools assisted the religious leaders in this issue. In the course of time, national feelings replaced the religious believes. While hearts of Armenians are imbued with sectarian senses rather than religious emotions, Armenian Comitadji succeeded easily in influencing religious men and referred to Turks with disgust [3]. Armenian tableaus occupied the most valuable places in schools. The Ottoman Tughras were took down and replaced with Armenian coat of arms, Armenian maps and Martini and Mauser rifles. Bombs were acquired and men were sent to Russia, Europe and America for training on bomb production [4].

In the Ottoman Armenian society there was also a class of bankers and usurers, called “Amira”. Amira class had more effect on the Armenian community than the Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul. [5]

Well, then why did Armenians emigrate? According to some Armenian researchers, Armenians emigrated for various reasons such as political factors, environmental factors, extradition to home country, economic and educational factors and temporary emigration. [6] As for Oshagan Minasyan, Armenians decided to emigrate because of political pressure and religious persecution and in order to improve their economic conditions and to receive good education [7]. According to Armenian historian Robert Mirak, the first factor that prompted Armenians to think of emigrating in 1900s was merchants’ lack of freedom to travel, secondly, high taxes and thirdly, fear of being massacred [8]. And according to McCarthy, a significant number of Armenians emigrated for economic reasons [9].

What Armenians deduce from political factors is the propagation of being exposed to massacre. However, same people acknowledge that in the mentioned period, emigrants temporarily arrived in America for various reasons, including political pressure [10]. When American and European newspapers of that period are scrutinized, it is seen that thousands of massacre reporting and the number of Armenians killed were published. Numbers in the propaganda articles and the comparison of that period’s Armenian population is another subject matter.

According to the detections of the Ottoman Empire, Armenians are people who, in order to acquire citizenship, declared authorities of the foreign country that they were instrumentalized by emigrant defenders with evil intent and that they chose to emigrate and live in misery in order to get rid of training and tuition they received in their countries, but at the same time they are the ones who, after pronouncing their ideas in areas they visited, returned to the Ottoman territory as a foreign country citizen and pursued detrimental activities [11]. As for the training and tuition matter, which was claimed by Armenians to be the reason of their emigration, the Ottoman Empire did not mistreat its minorities. As a matter of fact, in 1864, Paris Embassy sent 22 students abroad for education on the condition that they would be appointed to official posts upon return [12].

On the contrary, there was no hindrance to training and tuition and when the activities (establishing churches, opening schools and colleges) of American missionaries improved and extended in 1880s, there was an increase in Armenian emigration from all provinces, particularly Harput (40 %), and emigrants were mostly singles (95 %) [13]. Leaving their families in homeland in 1834, young singles and males mostly went to New York for education [14]. While majority’s aim was receiving religious education, students left for studying science and engineering [15]. According to the letter written by O. P. Allen, Missionary from Eastern Turkey Mission of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Mission (ABCFM), to Doctor Judson Smith in August 12, 1890, missionaries were not content with the idea of traveling to the America for education. He stated that they could not make progress as they could not reach villages, that they primarily were not in need of theology graduates in the area and that it was appropriate to have experienced volunteers with basic Christian doctrines [16]. O. P. Allen states in his letter dated 30 March that they were awaiting females to carry out activities for women and that it was compulsory to educate women in order to achieve lasting results. Missionaries are aware of the fact that children, who are future adults, should be targeted first and that children trained in mission houses would become soldiers who dedicate their lives for the sake of missionary activities when they are taught all sorts of difficulties in life. Missionaries are pleased to turn over their missions to safe hands. However, those who went to America to receive education make up one of the cases which caused the Missionaries to lose their hopes. Willingness of those young people going to America to stay there and their efforts to live as workers are both a source of disappointment and embarrassment for missionaries. What is important for the missionaries is to find an answer to how can sufficient number of and qualified local missionaries be trained and how it can be made possible for them to stay on the territories they are living on.17 In a letter he wrote on January 26, 1892, missionary O.P. Allen also gave the list of those who went abroad though they had found it inappropriate. Emigration of these people to America hinders the smooth conduct of affairs in Turkey. Armenians misled the Missionaries. Missionary O.P. Allen expressed that some of them were with them owing to financial concerns and they were not trustworthy. Many of them, after fulfilling significant tasks within the Mission, deceived the Missionaries and changed direction. Missionary O.P. Allen believes that it will be better if those young people, whom he thought would remain in the Mission but who decided to receive theological training in America, receive that training in Turkey. Although the missionaries oppose Armenians’ move to America, they have not thought of preventing them. They were concerned by the fact that they would be able to find a place in the Eastern Mission only for 10-15 individuals who had received training abroad, and would not know where to assign tens of them upon returning; they needed self-sacrificing and giving individuals to assign at positions which those, studying in and returning from America, would look down on. Since a great part of the people live in villages, those having studied abroad would not want to go to these places. Moreover, Missionary O.P. Allen believes that the officials working at major churches in Turkey are trained by Missionaries and the training received abroad is no more good; that many of young people unfortunately believe that they will go to better places, and that if they set up a system similar to the one in America, they will get away from the targeted mass.18

Not all the emigrant Armenians settled in America. Doctor Melcon Altounian, who studied medicine in Philadelphia, worked as college doctor in Merzifon in the 1890s. Professor A.G. Sivaslian came back after his three-year doctorate education at Carleton College on math and astronomy in 1894.19

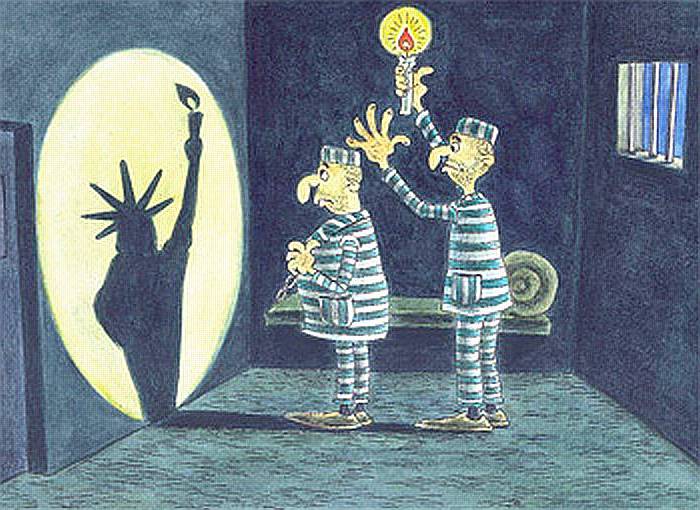

According to the Ottoman State officials; Armenians, with a view to benefit from the privileges of being a US citizen in the Ottoman State, went to America through various ways and changed nationality and then returned their homelands. In this way, they tried to evade any punishment due to their unlawful activities and any sanctions in the Ottoman laws.20 While America is equal to the high ideal of abundance, goodness and freedom21, most of the Armenians coming for educational, economic and partially political purposes regarded America as a temporary place of wealth, business and work. Most of the Armenians did not think of settling in the USA and they planned to come back from the USA after acquiring the wealth sufficient for their families to survive. On the other hand, those who found favorable socio-economic conditions in the USA increasingly settled there. Meanwhile, Armenians did not cut off their relations with their homelands and supported their relatives’ and associates’ emigration to the USA.22

According to the Armenian daily Gotchnag of November 10, 1904, the Armenian migration is divided into three periods as the students’ period of 1848-1875, the commercial period of 1875-1896, and the workers’ period of 1896-1904. Certain Armenian writers combined the first and second periods and divided the migration into two periods.23 In fact; the phenomenon of migration is basically divided into two periods as the migration under the influence of missionaries and the migration under the influence of Armenians. The first period was the period which missionaries caused in order to spread their sects and which they were mostly unable to control. The second period, on the other hand, was realized owing to the Armenian dreams of living in better conditions, the security concerns as well as the influence of the Armenian organizations. During the second period, which was quite long, social and political influences dominated one another from time to time.

Some of the Armenians went to America during the Ottoman-Russian War in 1877-78 in order to earn money and come back to their homelands. Only a very small number of them returned.24 Owing to the economic crisis suffered in the wake of the 1877-78 Ottoman-Russian War, artisan and merchant Armenians emigrated and the economic, social and political developments in America after the American Civil War (1861-65) encouraged Armenians to migrate to this country. In the 1880’s, wealthy Armenians mostly migrated to Europe25. A document dated 1896 states that there were lots of people who went to America to engage in commercial activities26. After the signing of trade agreement dated 1830, Armenian tradesmen from Izmir and Istanbul opened offices particularly in New York, Boston and Chicago27.

Seeing that the inclination of missionary American families to take male and female local Armenians to America together with themselves resulted in emigration to America, this practice was banned by the Ottoman State. Diplomatic correspondence took place between the USA and the Ottoman State on the issue29.

Armenian institutions and charity organizations in the USA made efforts for the mass migration of Armenians30.

America had also been a political shelter for members of revolutionary Armenian party members31. The families, who had been left behind by those who had emigrated to America and had changed their nationality, constituted one of the reasons of rising migrations. Efforts for uniting families continued and led to correspondence between the two countries32. Those who went for purposes of education and trade found the conditions in America favorable and strived to bring their families to this country and informed their relatives about emigration and thus facilitated migration33.

Some Armenians who had taken part in the events on the Ottoman territories stated that they had left the country on their own will and some stated that the reason for their leaving was mistreatment34. There were also some Armenians who decided to migrate for fear of safety. Also, it is understood from available archive documents that there were attempts of migration through the abuse of security issue35. To be able to attain their objectives, Armenian revolutionary organizations inflicted pain on their own people as well. They wanted to take money from wealthy Armenians and they killed those people unless they could receive their money36. The priest Mampre was killed in Uskudar district, Hachik – a lawyer – was killed in Topkapi district, Dikran Karagozyan was killed on Galata Bridge, Apik Uncuyan – a merchant – was killed in Galata neighborhood and Sebah – a lawyer – was killed at the Gate of Havyar Hani in Galata neighborhood37. These organizations also disturbed those who went abroad and a wealthy Armenian individual based in Europe whom they had asked for money, responded them saying “I do not want to be the killer of my country with my own money”. Jamharyan who was running an Armenian orphanage in Moscow and Bakalyan who was living in Novorossiysk were also killed for the same reason. Merchant Balyozyan from Izmir was killed again for the same reasons. They even killed their supporters who complained about these actions38.

Armenian party representatives collected donations by force and sold the weapons which had previously been given to Armenian citizens living in the cities of Sason and Mus, and they sometimes led to the loss of household goods, livestock and herds of Armenians39. These actions of terrorizers continued in spite of the fact that an Armenian State was founded. As we understand from documents belonging to Dashnaks, Armenian villagers were subjected to incredible violence by the Armenian government. For example, it was recorded in official documents that V. Agamyan, the commissary of the Dashnaktsuthiun government, punished people and executed them by shooting without any investigation or court trial, with the pretext of preventing desertions from the army. Agamyan gathered the wives, mothers and sisters of those individuals accused of desertion, he completely undressed them and forced them to imitate goose step in the public square of the village before all the village people. Then this Dashnak official beat the naked women and he kept them in water for many hours. Later Agamyan ordered the arrest of these women and he raped young women and girls at night40.

A paper published in Germany wrote that, Muslims and Armenians in Erzurum migrated from this region in 1893 because of the drought. Although the Ottoman Administration had told that there were individuals who went to Russia but they could not have found out people who went to America, it is possible that there were also people who went to America at that period41. It was determined that because of the harsh winter conditions and the events experienced in the years 1895 and 1896, “poverty and misery had inflicted the people from all walks of life, commercial activities and handicraft businesses could not be maintained, agricultural activities stopped, thousands of people wandered idly on the streets like vagabonds”42. All these factors strengthened people’s consideration of migration and urged them to leave the country.

Also the Armenians who had committed ordinary crimes considered emigration as a way of escape. An Armenian individual called Agop embezzled 39,950 liras in Diyarbakir and went to Istanbul, and after dealing with trading of zinc for three years, he migrated to America together with his family.43 Similarly, according to what Mr. Mavroyeni, Ambassador to Washington, said; there were applications to local authorities for the arrest of Cideciyan who had run away to New York after stealing 1,900 liras in the province of Van.44

Some people, as they saw the money earned by those who went to America, also wanted to emigrate, and the desire to live in better conditions caused them to emigrate.45

As a result, we can sum up the reasons for the Armenians to migrate to America as follows:

1. Willingness to receive education-training with the encouragement of missionaries,

2. Desire to overcome economic problems and to live in better conditions,

3. Objective of becoming wealthy,

4. Willingness to trade,

5. Encouragement by the Armenians in America,

6. Considering America as a political shelter,

7. Uniting the separated families,

8. Desire to live in a more secure environment,

9. Willingness of the criminals to evade justice.

B. Viewpoint of the Ottoman State about Emigration

The Ottoman State presupposed the results of the emigration and took some measures accordingly. New York Sehbenderligi (Consulate General)46 stated on May 22, 1893 that Armenians who were in America wanted to bring their families and if they succeeded they would certainly go further in their harmful activities. According to the Sehbender (Consul General), they should not be allowed to bring their families and also flees should be prevented. The families of Manuk Zarunyan (Derunyan?), one of the leading members of the Hinchak society from the village of Percenic, province of Mamuret-ul Aziz and Citciyan from the village of Icme should never be allowed to emigrate. Because the above-mentioned individuals were the directors of the mischievous activities in America.47

Upon this attitude of the Ottoman State, the US Department of State asked the reasons for the prohibition brought by the Ottoman State to the Armenians’ change of nationality to become American nationals in 1894. The Embassy notified the Department of State that those who sold their properties and went to America to settle together with their families were allowed to go; however, the aim of the Armenians was to obtain a foreign passport and then come back to the their homelands and facilitate their harmful activities.48

In 1891, Mr. Mavroyeni, Ambassador to Washington, informed Foreign Minister Sait Pasha that the emigration by the Armenians to America had reached dangerous dimensions.49 Ambassador Mr. Mavroyeni, who most came face to face with the Ottoman State’s Armenian problem, proposed to Foreign Minister Turhan Pasha to do the opposite of what the Armenians had asked, not to prohibit migration and not to accept back those emigrating, in response to a proposal by the daily Haik in 1895 which demanded that the migration of the Armenians be prevented.50

Migration is a phenomenon which cannot be prevented completely. Prohibition leads to illegal ways. In fact, the prohibition brought by the Ottoman State to migration did not prevent the emigration of the Armenians and it caused them to change nationality without permission. This brought the problem of nationality to the fore and thus the relations between the two countries occasionally turned out to be tense. The Ottoman State, just like the other European countries, tried to solve this problem by allowing those migrating to America to settle there by selling all their properties and taking their families with them.51 In 1896, according to the Ottoman State, it is inconvenient for US citizens of Armenian origin to return the Ottoman lands. In addition, their families should be permitted to travel to America. Because if not permitted, it is feared that Armenians, who are unable to return the Ottoman lands, can in grief do any evil so long as they are also not permitted to take in their families. However, while Armenians were prohibited to travel to America by the minutes of the Council of Ministers, dated June 23, 1896, it was identified that some Armenians traveled to America with commercial or other purposes, acquiring a European passport. And by reaping benefits, some officials help Armenians to run away. Since the desired result was not achieved on account of that, it was approved to permit Armenians willing to travel to America on condition that they never return and sell their properties in the Ottoman State and totally rupture their relationship with it [52].

In addition, problem of sending abroad families of those people, who emigrated through changing their nationalities, continued. The Ottoman Government avoided permitting external travels of families of Ottoman subjects [53], who left the state for trade, in order not to create precedent for the other Armenians [54]. It was decided to hinder would-be emigrants since the political and territorial significance of the money, sent from America by the most useful section of the nation to their relatives, could affect the other section [55].

The Ottoman State acknowledged that in 1903, Armenians were advised by the Government not to emigrate, but that it did not work [56]. It was detected that in 1907 Mount Lebanese, Syrian, Armenian, Bulgarian, Albanian and Greek Cypriots other than Turks and Kurds traveled to America and that people emigrated to America also from Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, Italy and Hungary. It was found out that those people returned in a miserable condition as they could not find any jobs. For this reason it was decided that emigration of the Ottoman subjects to America is not appropriate and that it was decided to take the necessary measures to hinder them from doing so [57].

Migration policy was changed after the declaration of the Constitutional Monarchy. Following the Armenian riot in 1894, the prohibition by the former administration on the travel of Armenians to America was abolished with the declaration of the Constitutional Monarchy and everyone was set free to go wherever they liked [58].

C. America’s Standpoint on Immigration

The American Government knew that the most significant reason of the Ottoman State’s hindrance of Armenian emigration was the intention of Armenians to reap benefits from American protection by acquiring American nationality. While also being aware of the goal of Armenians to break off some Anatolian provinces and establish an Armenian State, the American Government did not try to hinder Armenian immigration [59].

Needing to increase its population and especially qualified employees, America passed a law on May 23, 1896, provided that it had no relation with the Ottoman State, though it was concerning it. Under that law, people who are not above 16 and who lack literacy shall not be admitted to enter America as immigrants. People who are admitted as immigrants shall possess the right to take their wives, little children, grandchilds, fathers, mothers and their ancestors with themselves or afterwards [60]. However, the law was vetoed by President Grover Cleveland on the ground that it was against equality [61].

Inconveniencing acceptance conditions of immigration, the American Government did not admit some of the immigrant Armenians on pretext that they lacked necessary features. It was found out by Foreign Ministry in 1910 that these people were wretched and miserable [62].

C. Armenian View of Migration

The Armenian desire to migrate has economic, social and political reasons. Yusuf Bey, the Council to Barcelona, reported that the migrants who had escaped abroad in 1899 decorated their reasons to migrate with stories of massacres, oppression and violence.[63] The determinations of Yusuf Bey were accepted by the American Government and the public opinion before they had been investigated. Even today, we are faced with these made-up stories as if they were real ones.

The missionaries of the New York Armenian Charity Association tried to assist the migration especially by using Barton[64]. During a meeting held at the Sanzal Music Hall in Chicago in 1896, Garaterin (?), from the Chicago Armenian Charity Organization, informed the Chicago Consulate that the migration of Armenians to America and Canada had been decided on the condition that their needs were met.[65] Again, some pro-Armenian Railway Companies supported the Armenian migration to America [66]. The missioner J. Rendel Harris, mentions in his letter dated April 12, 1896 that he got the promise from the owner of a rich American railway company who arrived in Izmir on a French steamer to settle the Armenians the western states of America if at least one thousand of them had been brought to New York. [67]

According to an Armenian paper called “Haik” issued in America, Hunchak and Cheraz parties supported the Armenian migration because they were expecting financial aid.[68] From the reports by the detection office assigned by the Ottoman Empire to watch Armenians in Boston, Armenian parties aimed at raising aids through ensuring Armenian migration to America.[69] Again the same newspaper wrote in 1895 that the Armenian population had to be increased, Armenian migration be banned, and the had to go back to the Ottoman territories.[70]

But the Anatolian Armenians did not support the migration and complained about Harput envoy’s encouraging Armenians to migrate. [71]

In 1911, the Armenian Patrick claimed that the promissory notes suggesting that those who had changed nationality would not return had been signed under obligation, and that just as it was the case in being the national of the Ottoman Empire was the natural right each Ottoman citizen, the right to go to another country was an open right of freedom protected by the Kanun-i Esasi (the Constitution) and by the related laws, and wanted those who had been denaturalized to be re-naturalized.[72] Although the Patrick supported the Armenian migration, he also wanted those, who would like to, to be re-naturalized. Thus, he preferred both Armenians to avoid from an investigation by the Ottoman Empire thanks to owning American passports and to prevent the population fall in the Armenian-inhabited cities.

Conclusion

This migration activity taken place in the 19th century satisfied neither the Armenian nor the Ottoman Empire. Armenians themselves are liable for the difficulties they suffered from. Armenians try to blame the State, and even the Turks for the hardships they experienced. They never mentioned their own faults and are continuing to mislead the public opinion.

[1] From Kamuran Gurun, Ermeni Dosyası, 5. Baskı, S.Y: Rustem yay. 2001, ss. 89-90, C. Oscanyan, The Sultan and His People, New York, 1857.

[2] Greek Cypriots and Jews are located in the position of the Armenians in west of the Ottoman territories. For more information, see Ali Guler, XX. Başlarının Askeri ve Stratejik Dengeleri Içinde Turkiye’deki Gayri Müslimler (Sosyo – Ekonomik Durum Analizi), Ankara: ATASE Yay.1996.

[3] Viladimir Mayewsky, Yabancı Gozuyle Ermeni Meselesi [Armenian Issue In The Eyes of Foreigners], Trans. Major Sadık Ahmet, Trans. from Ottoman language Eyup Sahin, Ankara: Askerlik Dairesi Baskanligi Yayinlari [Publications of Military Recruitment Department], 2001, p. 4-5.

[4] Cemal Anadol, Tarihin Isıgında Ermeni Dosyası [The Armenian File In The Light Of History], 3rd Edition, İstanbul: IQ Culture and Arts Publications, 2002, p.113.

[5] Mirak Robert, Torn Between Two Lands: Armenians in America 1890 to World War I, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983, p. 9.

[6] Meline Karakashian and Gevorg Poghosyan, “Armenian Migration and Diaspora: A Way of Life”, Leonore Loeb Adler and Uwe Gielen, Ed., Migration: Immigration and Emigration in International Perspective, Westport: Praeger/Greenwood, 2003, p. 225-242.

[7] Oshagan Minassian, A History of the Armenian Holy Apostolic Church in the United States (1888-1994), Unpublished Doctorate Thesis, Boston: Boston University School of Theology, 1974, p. 41-42.

[8] Robert Mirak, Torn Between…, p. 50-51.

[9] Justin McCarthy, Olum ve Surgun [Death and Exile], 3rd Edition, Istanbul: Inkilap Kitabevi, 1995, p. 134.

[10] Oshagan Minassian, A History of …, p. 62.

[11] BOA. Y. PRK. AZJ, File 47, No:48.

[12] Osmanlı Belgelerinde Ermeniler [Armenians in Ottoman Documents, (Catalog) , Istanbul: Publication of the General Directorate of State Archives, Department of Ottoman Archive, Vol. 1, Doc. No: 158.

[13] Ercument Kuran, “Baslangictan Gunumuze Ermeni-Turk Iliskileri [Armenian-Turk Relationship from the Beginning to Date]” (Interview), Ermeni Sorunu Ozel Sayisi I [Armenian Question Special Issue I], İssue No: 37, Ankara: Yeni Turkiye, Jan-Feb 2001, p. 95; Knarik Avakian, “The History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America (From the Beginning to 1924)”, http://geocities.com/lira777/summaryE.html.

[14] Knarik Avakian, The History of …

[15] Oshagan Minassian, A History of …, p. 32.

[16] ABCFM Archive, ABC 16.9.7, Reel 695, Vol. 4.

[17] ABCFM Archive, ABC 16.9.7, Reel 695 (69), Vol. 8.

[18] ABCFM Archive, ABC 16.9.7, Reel 695 (78), Vol. 8.

[19] George E. White, “Adventuring with Anatolia College, The First College Decade, 1861-1940”, http://www.hastings.edu/html/library/rerumvol5_2firstcoldec.htm.

[20] BOA. Y. MTV. File 67, No: 31.

[21] Galust A. Galoyan, “The Armenian Question and International Diplomacy After World War I”, Armenian Perspectives: 10th Anniversary Conference of the Association Internationale Des Batudes Armbenienes, Richmond: Routledge, UK, 1997, p. 294 – 311.

[22] Knarik Avakian, The History of…

[23] Oshagan Minassian, A History of …, p. 27.

[24] Vahan M Kurkjian,, A History of Armenia, U.S: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America, 1958, p. 473.

[25] Knarik Avakian, The History of...; Some Armenians participated in the American civil war. Garabed Kaloustian, Baronig Mateosian and chief surgeon of the Philadelphia Hospital Simon Minasian served as doctor; Armenag of Khas, Narinian of Smyrna and Zora Tateosian served as soldiers. Oshagan Minassian, A History of …, p. 33.

[26] BOA. A. MKT. MHM. File 658, Nr. 42, Annex 3.

[27] Oshagan Minassian, A History of …, p. 34.

[28] BOA. Y. A. RES. File 80, Nr. 37, Annex 3.

[29] BOA. A. MKT. MHM. File 628, Nr. 44; Erdal Acikses, “An Assessment Regarding the Missionary Activities during the Ottoman Period (Examples from two Centers)”, the New Turkey, Special Edition 38, Ankara: March-April 2001, p. 943.

[30] See BOA. HR. SYS. File 2859, Nr. 52; Y.A. RES. File 80, Nr. 37.

[31] Knarik Avakian, The History of...

[32] At the Ottoman Archives there are too many documents regarding the subject. Some of those documents are as follows: BOA., Y. A. RES. File 80, Nr. 114; A. MKT. MHM. File 658, Nr. 29; ZB. File 315, Nr. 32; Y. A. RES. File 80, Nr. 37; A. MKT. MHM. File 658, Nr. 42; Y. PRK. ESA. File 17, Nr. 51; HR. SYS. File 2743.

[33] Isil Acehan, “From the Old World to the New One: On the First Muslim Migration from Anatolia to the USA”, East West, Nr.:32, Ankara: East West Pub. May, June, July 2005, pp. 221–238.

[34] The Armenian-French Relations in the Ottoman Documents (1879–1918), Volume I, Ankara: Directorate General of the State Archives, 2002, pp. 94 – 116.

[35] BOA. DH. MUI. File 8–3, Nr. 12.

[36] Erdal Ilter, “The Role of the Dashnak Party in the Armenian Uprisings (1892–1914)”, A friendly look up in history on the eve of the 21st Century, International Symposium on the Turco-Armenian Relations Ankara: Ataturk Research Center of Ataturk Higher Institute for Culture, Language and History Publications 2000, pp. 87–88 Sempat Gabrielyan, The Armenian Crisis and Regeneration, Boston: 1905, p. 94 –157, K.S.Papazian, Patriotizm Perverted, Boston, 1934, Leonard Ramsden Hartill, Men Are Like That, Indianapolis, 1928, p. 97-98; Erdal Acikses, “On the Role of the Migration in the Armenian Issue”, The Armenian Studies: 1. The Communiqués of the Turkey Congress, Volume II., Ankara: ASAM Armenian Research Institute Publications 2003, pp. 3–13.

[37] The Aims of the Armenian Committees and the Revolutionary Movements (Before and After the Declaration of the Constitutional Monarchy), Ankara: ATASE Publications 2003, p. 12.

[38] Esat Uras, The Armenians in the History and the Armenian Issue, 2. Edition, Istanbul: Document issue. 1987, p. 452; BOA. HR. SYS. File 2743, Nr. 65.

[39] Esat Uras, The Armenians Throughout the History...., p. 454.

[40] Mehmet Perincek, “The Dashnaksutyun reality in the Sources of the Dashnak and Soviet Armenia” November 23–25, 2005, Communiqué of the Gazi University Armenian Symposium, http://www.turksam.org/tr/ yazilar.asp?kat=45&yazi=646.

[40] Mehmet Perincek, “ The Dashnaktsuthiun Truth in Dashnak and Soviet Armenian Sources” 23-25 November 2005, Communique of the Armenian Symposium in Gazi University, http://www.turksam.org/tr/yazilar.asp?kat=45&yazi=646.

[41] BOA. Y. PRK. A. File 9, No: 21.

[42] Osmanli Belgelerinde Osmanli-Fransiz Iliskileri I [Ottoman-French Relations in Ottoman Documents I], p. 79

[43] BOA. ZB. File 419, No: 162.

[44] Osmanli Belgelerinde Ermeniler [Armenians in Ottoman Documents], Vol. 11, Doc. No: 113.

[45] Migrants returning their homes in wealthy clothes was received with admiration. Akram Fouad Khater, Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and The Middle Class in Lebanon 1870-1920, California: University of California Press, 2001, p. 57; In 1888, America sent 33.000 liras and in 1892 it sent 88.000 liras to Harput. Chiristofer Clay, “Labour Migration and Economic Conditions in Nineteenth-Century Anatolia”, Silvia Kedouire, Ed., Turkey Before and After Ataturk: Internal and External Affairs, London: Routledge, 1999, p. 1-32.

[46] Before the setting up of the Ministry of Commerce, Sehbender (Consul) was the official charged with taking care of commercial affairs and solving the disputes between tradesmen. When it was realized during the reign of Mahmud II that trade was coming under the control of foreigners, trade was divided into two and Muslim tradesmen were called “Hayriyye Tuccari” and non-Muslim tradesmen were called “Avrupa Tuccarı”. Hayriyye Tuccari were given certain privileges and one of them was chosen “sehbender”. Sehbenders were classified into four as chief sehbender, sehbender, deputy sehbender, sehbender clerk. In 1838, “Meclis-i Ziraat ve Sanayi (Agriculture and Industry Council) was established and its name was changed to “Meclis-i Umur-i Nafia (Public Works Council)” a few days later. In 1839, “Commerce Viziership” was established and this council was subordinated to it. The term “Sehbender” was later used as an equivalent of consul, a title for officials charged with guarding their own states’ interests in foreign countries. Since 1908, the term konsolos (consul) was used instead. M. Zeki Pakalin, Osmanlı Tarih Deyimleri ve Sozlugu [Dictionary of Ottoman Historical Expressions and Terms, Vol. III, Istanbul: Milli Egitim Bakanligi (Ministry of National Education), 1954, p. 316.

[47] BOA. Y. PRK. EŞA. File 17, No: 51.

[48] Osmanli Belgelerinde Ermeniler [Armenians in Ottoman Documents], Vol. 22, Doc. No: 22, Doc. No: 53.

[49] BOA. HR. SYS. File 2735, No: 29.

[50] Osmanli Belgelerinde Ermeniler [Armenians in Ottoman Documents], Vol 32, Doc. No: 30.

[51] BOA. A. MKT. MHM. File 533, No: 2.

[52] BOA. Y. A. RES. File 80, No: 114.

[53] BOA. A. MKT. MHM. File 658, No. 42, Annex3.

[54] BOA. A. MKT. MHM. File 658, No: 42, Annex4.

[55] BOA. Y. A. RES. File 55, No:53, Annex4.

[56] BOA. Y. PRK. AZJ. File 47, No: 48.

[57] BOA. Y. A. HUS. File 517, No: 41, Annex2.

[58] The Law on Citizenship: Article 6. BOA. DH. SYS. File: 67, Nr: 1–6; BOA. DH. MUİ. File: 8–3, Nr: 12, Lef 4; BOA. Y. A. RES. File: 68, Nr: 63.

[59] President Cleveland expressed this opinion in his annual speech. BOA. Y. PRK/ A/ File:8, Nr:66. The United States adopted in 1918 the law on denying entry to anarchists into the country. Edwin Munsell Bliss, Turkey and the Armenian Atrocities, Edgewood Publishing Company, 1896, p.549; Edith Abbott, İmmigration: Select Documents and Case Records, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1924, p. 231.

[60] Kuban Armenians were not included in this law. BOA. HR. SYS. File: 74, Nr: 49. Previously, on June 3rd, 1889, Mr. Mavroyeni, Armenia’s Ambassador to Washington, asked Blaine, the Secretary of State, to ensure the unproblematic landing of non-English speaking Turkish migrants in the presence of New York Sehbender; he then expressed his appreciation as his request was put into implementation on June 22nd 1889. Osmanlı Belgelerinde Ermeniler [Armenians in Ottoman Documents], Volume:7, Document Nr: 49, 57

[61] Sean Dennis Cashman, America in The Gilded Age, New York: New York University Press, 1993, p. 98–99

[62] BOA. ŞD. File: 2794, Nr: 3.

[63] Akram Fouad Khater, Home: Emigration..., p. 48

[64] They even suggested in 1896 to raise $ 1,000,000 through the “New York Times”. BOA. HR. SYS. File: 74, Nr: 28.

[65] The plan was to settle the Armenians on the non-agricultural parts of America and Canada. BOA. HR. SYS. File: 2859, Nr: 52

[66] BOA. Y. A. RES. File: 80, Nr: 37, Annex: 1

[67] J. Rendel Harris ve B. Helen Harris. Letters from the Scenes of the Recent Massacres in Armenia, London: James Nisbet & Co., Limited, 1897, p. 19

[68] BOA. Y. A. HUS. File: 285, Nr: 3

[69] BOA. HR. SYS. File: 2855, Nr: 68

[70] Osmanlı Belgelerinde Ermeniler [Armenians in Ottoman Documents], Volume: 32, Document Nr: 30

[71] Recep Karacakaya, Türk Kamuoyu ve Ermeni Meselesi [The Turkish Society and the Armenian Issue], İstanbul: Toplumsal Dönüşüm Yay. 2005, p. 135

[72] BOA. DH. SYS. File: 67, Nr:1–6.

Source: Ermeni Araştirmalari Dergisi [The Journal on Armenian Studies], Issue: 23-24, 2006, Dr. Ahmet AKTER

www.soykirimgercegi.com